I always wanted to be somebody

I should have been more specific. 1

Preface

Above the door in the LDS Family History Library in Sacramento, California, there is a sign that reads, “I think that I shall never see a finished genealogy.” That bit of bad poetry accurately describes the predicament of all confirmed genealogists. If we go back in history far enough, we are all related to each other and we never know when to say enough is enough. Every time a new piece of the puzzle is found it just seems to whet our appetite for more, and the chase is on again. Where it will all end is still in question, but this book is a snapshot of the present state of knowledge about our family origins.

“A chimpanzee with a stack of empty boxes and a banana hanging out of reach soon learns by his own experience. But man alone learns from the experience of others."2 This is why we study history. History is the accumulated knowledge of all of mankind’s experiences. This book is about our family history and in particular about how they experienced life from the 17th century to the end of WWII. As you will see sometimes the going was smooth, but mostly it is about struggles, and about constant migration from one country to another, or from one state to another as our ancestors strove to improve their lives. To better understand what their lives were about, I have included historical material about the places where they lived for each branch of the family tree.

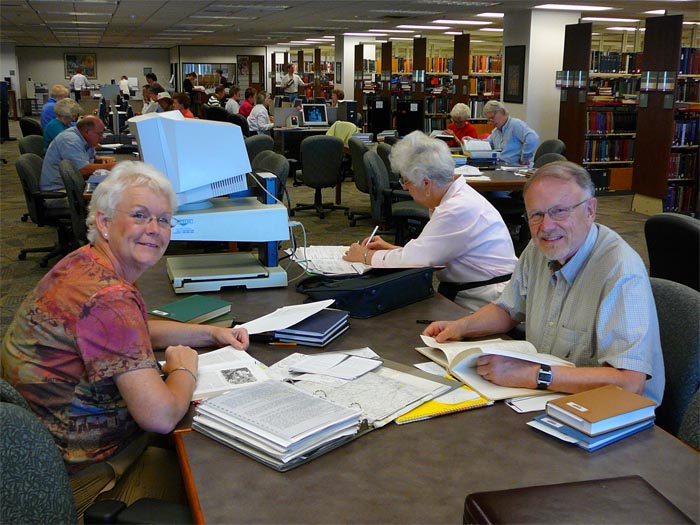

This project was started from scratch about 1998. At that time, I knew only a few last names of ancestors who lived before 1900, and nothing at all about their lives. I was fortunate that early on I crossed paths with two distant cousins, Robert Shively from Phoenix, Arizona, and Linda Chappell Curley from Bend, Oregon. Each was able to instantly fill in some very large gaps in the family history. Although progress slowed considerably after that, this project has been extremely rewarding. For a person like me who has had a lifelong love of mysteries, libraries, and history, genealogy has turned out to be the perfect hobby because it encompasses all three. Try to picture a comfortable library desk, deep in the stacks, with the musty smell of old leather and paper, surrounded by shelves of books and journals, all with stories to tell about history, traditions, and families. This is a genealogist’s heaven.

Donna

Gibson and Neil Elvick researching in the Family History Library in Salt Lake

City

Photo

by Jim Gibson

Of course some genealogical research also must be done on the computer or out in the field in county courthouses, but that is no less interesting. Every year there are more and more early county and state records being made available on the Internet and, although this is still spotty, some church records are also finding their way online. Baptismal, marriage, confirmation, and cemetery records are often the only available means of finding someone when searching governmental records has failed. Some of the unanswered questions in our family may ultimately be found as these records become available.

Today, one can search federal census records online and unlike in the past one doesn’t have to look line by line through endless strips of microfilm. But valuable as they are they are not totally complete. Almost the entire 1890 census was lost to fire and the senseless bungling of those whose responsibility it was to properly handle the fire damaged records. The military census and parts of a few state records are all that survived. Parts of the 1790 and 1800 census records have also been lost. There is still a question about whether they were destroyed when the British burned Washington during the War of 1812, or whether they were just misplaced. Some of these census records were pieced back together from copies that were sent to individual counties, but in some states the records are still incomplete. This is especially harmful to us because the Virginia records are in this category. The first federal census record for Virginia is 1810 and between 1790 and 1820 we had ancestors moving about in that state. Some state and county tax census records are available but mostly the data is sparse compared to other states.

Fire, that bane of the genealogist’s existence, has raised havoc with some of our searches. Church records burned by invading armies in Germany and courthouse and church fires in America have destroyed a great many historical records that pertain to our family. Especially damaging was the burning of the records from the Rockingham County Courthouse in Harrisonville, Virginia by General George Custer in a sweep through the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War. Although most of the records were ultimately saved the land records pertaining to our family were burned and among those not recovered. The many church fires in southeastern Pennsylvania almost certainly destroyed records of the Wise and MacMillan families. Almost all of the federal Revolutionary War military records went up in flames in the year 1800. Despite this, though, enough records have survived so that a fairly clear history of the family has emerged.

In the 1990’s the Broderbund software company began a project to record family trees that their customers had worked out on their Family Tree Maker software programs. This resulted in millions of names being submitted in thousands of family trees. Although the documentation for much of this data was often lacking and its accuracy questionable, it could connect you with other investigators and point you in different directions that you hadn’t thought of before. This is what put me in touch with several distant cousins who have been able to provide me with information on their particular branches of the family tree. Since then I have learned to search on my own through census records, church records, deeds, probates, passenger lists, county and state histories, military files, cemeteries, and just about any kind of record you can hope to find in a county courthouse.

It never ceases to amaze me what our ancestors accomplished. We often look forward with distaste to something like a trip on a crowded airliner, or a cross country trip in a car, but in decades and centuries past our forefathers making such trips had to either walk those distances or ride for days or weeks in vehicles pulled by oxen or horses. Often there were just wagon tracks to follow. They had to carry their own provisions and prepare their meals using only basic foodstuffs and coarse utensils. Sometimes children were born on these trips. Those that had to cross the Atlantic often had miserable conditions to contend with on board the ships. There was little personal space, and no privacy. Food and water were of poor quality and often ran short. When our ancestors made that trip in the 18th century the voyage could take two to three months. Disease and death were rampant. And at journeys end there was often the task of building shelter and planting crops to sustain just the barest of existence. Some of our family members were faced with this type of situation more than once during their lifetime. Sometimes it was extreme poverty that forced a family to uproot itself. Sometimes it was just coming to America or on to a different state looking for a better life. Some of our family faced even much worse circumstances in that they also faced religious persecution.

To have endured what they did and survived was an outstanding accomplishment. To have survived all this and prospered is to me a miracle. We, the succeeding generations, are the beneficiaries of their hardships and sacrifices. It is therefore to the memories of these people, our ancestors, that I dedicate this work.